What are securities in finance? This question opens the door to a fascinating world of investment and financial markets. Securities represent a broad range of financial instruments, each with its own unique characteristics, risks, and potential rewards. Understanding these instruments is crucial for anyone looking to navigate the complexities of the modern financial landscape, whether it’s for personal investment or a deeper understanding of the global economy.

From the relatively straightforward concept of owning a share of a company’s stock to the more intricate world of derivatives, the types of securities available are diverse. This exploration will delve into the various categories – equity securities, debt securities, and derivatives – examining their defining features, inherent risks, and the roles they play in capital formation and economic growth. We will also touch upon the regulatory frameworks designed to protect investors and maintain the integrity of the markets.

Definition of Securities

Securities are financial instruments that represent ownership in a company or a debt owed by a company or other entity. They are essentially tradable assets that derive their value from an underlying asset or claim. Investing in securities offers a way to participate in the growth and profitability of businesses or to lend money and earn interest.

Securities represent a broad range of investment options, each carrying different levels of risk and potential return. Understanding the various types and characteristics of securities is crucial for making informed investment decisions.

Categories of Securities

The securities market encompasses a wide array of instruments. Broadly, they can be categorized into two main groups: equity securities and debt securities. These categories, in turn, encompass various sub-types, each with its own unique features and risk profiles.

- Equity Securities: These represent ownership in a corporation. The most common type is common stock, which grants shareholders voting rights and a claim on the company’s assets and earnings. Preferred stock, another type of equity security, offers a preferential claim on dividends and assets in case of liquidation, but typically doesn’t carry voting rights. Examples include shares of Apple Inc. or Microsoft Corporation.

- Debt Securities: These represent a loan made to a corporation or government. The borrower promises to repay the principal amount plus interest over a specified period. Examples include bonds issued by governments (e.g., U.S. Treasury bonds) or corporations (e.g., corporate bonds). Other debt securities include notes, debentures, and commercial paper.

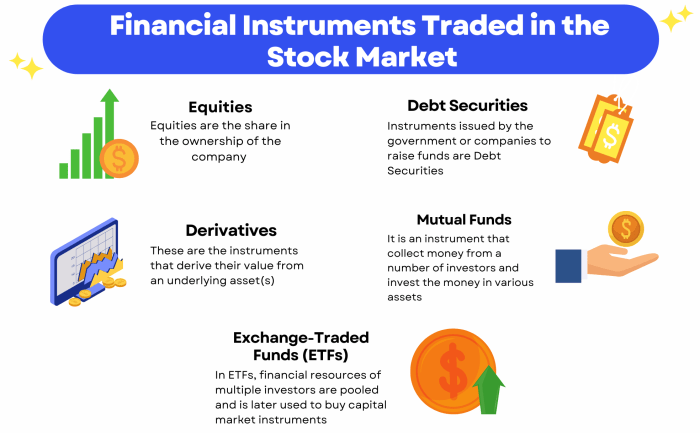

Beyond these core categories, other types of securities exist, including derivatives (options, futures, swaps), which derive their value from an underlying asset, and investment funds (mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs)) which pool money from multiple investors to invest in a diversified portfolio of securities.

Key Characteristics of Securities

Several key characteristics define a security. These features help determine its value, risk profile, and suitability for different investors.

- Transferability: Securities are generally easily transferable, meaning they can be bought and sold in the market, providing liquidity to investors.

- Divisibility: Securities can be divided into smaller units, making them accessible to a wide range of investors with varying capital amounts. For example, shares of stock can be bought and sold in fractions.

- Standardization: Many securities are standardized, meaning they have similar features and terms, facilitating trading and comparison.

- Expected Return: Investors purchase securities with the expectation of earning a return, either through dividends (equity), interest (debt), or capital appreciation (increase in market value).

- Risk: All securities carry some level of risk, representing the possibility of losing some or all of the invested capital. The level of risk varies significantly depending on the type of security and the issuer’s financial health.

A security is a tradable financial asset representing ownership or a debt obligation.

Types of Securities

Securities represent a broad range of financial instruments used for investment and trading purposes. Understanding the different types of securities is crucial for investors to make informed decisions and manage their portfolios effectively. This section will categorize the major types of securities, highlighting the key distinctions between equity and debt securities and exploring their associated features and risks.

Equity Securities

Equity securities represent ownership in a company. The most common type is common stock. Investors who purchase equity securities become shareholders, and their returns are directly tied to the company’s performance. If the company prospers, the value of the shares increases, generating capital gains for investors. Conversely, if the company struggles, the share value may decline, resulting in potential losses. Preferred stock is another type of equity security, offering features that differ from common stock, such as dividend preferences and priority in liquidation. However, preferred stockholders generally do not have voting rights.

Debt Securities

Debt securities represent a loan made to a company or government. The issuer of the debt security promises to repay the principal amount plus interest over a specified period. Examples include bonds, treasury bills, and notes. These securities offer a fixed income stream, making them attractive to investors seeking predictable returns. However, the returns are typically lower than those offered by equity securities, and the investor’s principal is at risk if the issuer defaults on its payments.

Comparison of Equity and Debt Securities

Equity and debt securities differ significantly in their risk-reward profiles. Equity securities offer higher potential returns but also carry greater risk. Their value is directly linked to the company’s success, which can be highly volatile. Debt securities, on the other hand, offer lower potential returns but are generally considered less risky. The fixed income stream provides predictability, but the investor’s principal is still subject to risk if the issuer defaults. The choice between equity and debt securities depends on an investor’s risk tolerance and investment goals. A conservative investor might favor debt securities, while a more aggressive investor might opt for equity securities.

Features and Risks of Common Stock

Common stock offers voting rights, allowing shareholders to participate in company decisions. However, dividends are not guaranteed, and the value of the stock can fluctuate significantly based on market conditions and company performance. Investing in common stock carries significant risk, but the potential for high returns can be attractive to investors with a higher risk tolerance. For example, investing in a high-growth technology company could yield substantial returns, but it also carries a higher risk of loss compared to investing in a more established, dividend-paying company.

Features and Risks of Bonds

Bonds offer a fixed income stream through regular interest payments (coupon payments) and the repayment of the principal at maturity. However, bond prices can fluctuate based on interest rate changes. If interest rates rise, the value of existing bonds will fall, and vice-versa. The risk of default, where the issuer fails to make payments, is also a significant consideration. Government bonds are generally considered less risky than corporate bonds due to the perceived lower risk of default by a government. However, even government bonds are subject to interest rate risk.

Equity Securities

Equity securities represent ownership in a company. Unlike debt securities, which represent a loan to a company, equity securities grant the holder a share of the company’s assets and earnings. This ownership stake comes with certain rights and privileges, which vary depending on the type of equity security held. The two most common types of equity securities are common stock and preferred stock.

Common Stock and Preferred Stock

Common stock and preferred stock are the two primary types of equity securities. Common stock represents the most basic form of ownership in a company. Common stockholders have voting rights in company matters, such as electing the board of directors, and they share in the company’s profits through dividends (if declared) and the appreciation of the stock’s value. Preferred stock, on the other hand, represents a class of ownership that typically has preference over common stock in terms of dividend payments and asset distribution in the event of liquidation. However, preferred stockholders usually have limited or no voting rights.

Examples of Equity Ownership

Owning shares of a company’s common stock directly translates to ownership of a portion of that company. For example, if a company has 1 million shares outstanding and you own 10,000 shares, you own 1% of the company. This ownership gives you a claim on a proportionate share of the company’s assets and earnings. If the company is successful and its value increases, the value of your shares will also increase. Similarly, if the company distributes dividends, you will receive a portion of those dividends based on your share ownership. Consider Apple Inc. If you purchase shares of Apple common stock, you become a part-owner of Apple, albeit a very small part. Your ownership entitles you to potential dividends and a share in the company’s overall growth.

Comparison of Common and Preferred Stockholder Rights

The following table summarizes the key differences in rights and privileges between common and preferred stockholders:

| Feature | Common Stock | Preferred Stock |

|---|---|---|

| Voting Rights | Generally, yes; one vote per share. | Usually limited or no voting rights. |

| Dividend Payments | Dividends are paid at the discretion of the board of directors; no guaranteed payment. | Dividends are usually paid at a fixed rate, and are typically paid before common stock dividends. |

| Asset Distribution in Liquidation | Receive assets after preferred stockholders are paid. | Receive assets before common stockholders. |

| Price Volatility | Generally more volatile than preferred stock. | Generally less volatile than common stock. |

Debt Securities

Debt securities represent a loan made by an investor to a borrower (typically a corporation or government). Unlike equity securities, which represent ownership, debt securities represent a creditor relationship. Investors receive periodic interest payments and the repayment of the principal at maturity. This section will delve into the characteristics of various debt securities and explore the risk-return trade-off associated with them.

Characteristics of Bonds, Notes, and Debentures

Bonds, notes, and debentures are all types of debt securities, but they differ in their maturity and the level of security offered to the investor. Bonds typically have longer maturities (generally over 10 years), notes have shorter maturities (typically 1 to 10 years), and debentures are unsecured bonds, meaning they are not backed by specific collateral. The interest rate, or coupon rate, is usually fixed for the life of the bond, note, or debenture, though some may have floating rates tied to a benchmark. The issuer’s creditworthiness significantly impacts the interest rate; higher-risk borrowers will need to offer higher interest rates to attract investors.

Maturity and Interest Payments

A crucial characteristic of debt securities is their maturity date. This is the date on which the principal amount (the original loan amount) is repaid to the investor. Interest payments, also known as coupon payments, are typically made periodically (e.g., semi-annually or annually) until maturity. The coupon rate determines the amount of each interest payment. For example, a bond with a $1,000 face value and a 5% coupon rate paying semi-annually would make payments of $25 ($1000 * 0.05 / 2) every six months. The timing and amount of these payments are specified in the bond’s indenture (the legal agreement between the issuer and the bondholder).

Comparison of Debt Securities Based on Risk and Return

The risk and return profile of debt securities varies considerably depending on several factors, including the issuer’s creditworthiness, the maturity date, and the presence or absence of collateral. Generally, longer-maturity securities carry higher risk due to increased interest rate volatility and the longer period before principal repayment. Unsecured debt (like debentures) is riskier than secured debt (like mortgage-backed bonds). Higher risk is typically associated with a higher potential return to compensate investors for taking on more risk.

| Debt Security Type | Risk | Return | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treasury Bonds | Low | Low | U.S. Government Bonds |

| Corporate Bonds (Investment Grade) | Medium | Medium | Bonds issued by large, financially stable companies |

| Corporate Bonds (High-Yield) | High | High | Bonds issued by companies with lower credit ratings |

| Municipal Bonds | Medium-Low to Medium | Medium-Low to Medium | Bonds issued by state and local governments |

Derivatives

Derivative securities are financial contracts whose value is derived from an underlying asset. This underlying asset can be almost anything of value, from stocks and bonds to commodities like gold or oil, or even interest rates or weather patterns. Unlike owning the underlying asset directly, investing in derivatives allows investors to speculate on the future price movements of that asset without actually owning it. This offers both opportunities and significant risks.

Derivatives are powerful tools that can be used for hedging (reducing risk) or speculation (increasing risk). Hedging involves using a derivative to offset potential losses from an existing position. For example, a farmer might use futures contracts to lock in a price for their harvest, protecting them from price fluctuations. Speculation, on the other hand, involves using derivatives to bet on the future direction of an asset’s price, aiming for a large profit but accepting the possibility of significant losses. Understanding the nuances of derivative contracts is crucial for navigating their complexities.

Options

Options contracts give the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specific price (the strike price) on or before a specific date (the expiration date). There are two main types of options: call options (the right to buy) and put options (the right to sell). For example, a call option on Apple stock with a strike price of $180 and an expiration date of December 2024 gives the buyer the right to purchase Apple stock at $180 per share anytime before December 2024. If the price of Apple stock rises above $180 before the expiration date, the option becomes profitable. Conversely, a put option allows the holder to sell the underlying asset at the strike price.

Futures

Futures contracts are agreements to buy or sell an asset at a specific price on a future date. Unlike options, both parties in a futures contract are obligated to fulfill the agreement. This means that if you buy a futures contract for oil, you are obligated to buy that oil at the agreed-upon price on the specified date, regardless of the market price at that time. Futures contracts are frequently used by businesses to hedge against price fluctuations in commodities or other assets. For instance, an airline might use futures contracts to lock in a price for jet fuel, mitigating the risk of rising fuel costs.

Swaps

Swaps are agreements between two parties to exchange cash flows based on the value of an underlying asset. A common type of swap is an interest rate swap, where two parties agree to exchange interest payments based on different interest rate benchmarks. For example, a company might enter into an interest rate swap to exchange its variable-rate debt for a fixed-rate payment, reducing its exposure to interest rate risk. Currency swaps are another common type, allowing companies to exchange cash flows in different currencies.

Risks and Potential Benefits of Investing in Derivatives

Investing in derivatives carries significant risks, primarily due to their leveraged nature. Small price movements in the underlying asset can lead to substantial gains or losses in the derivative contract. The potential for unlimited losses in some derivative contracts is a major concern. Furthermore, the complexity of derivative instruments requires a thorough understanding of their mechanics and associated risks. However, derivatives can also offer significant benefits. They provide investors with tools for hedging, speculation, and managing risk effectively. Careful risk management and a deep understanding of the market are crucial for successful derivative trading. Investors should only engage in derivative trading if they have the necessary knowledge and risk tolerance.

Securities Markets

Securities markets are the crucial marketplaces where the buying and selling of securities take place, facilitating the flow of capital between investors and businesses. These markets are vital for economic growth, enabling companies to raise capital for expansion and investors to diversify their portfolios and earn returns. The structure and function of these markets are governed by a complex interplay of supply and demand, regulation, and market participants.

Securities markets are broadly categorized into primary and secondary markets, each playing a distinct but interconnected role in the overall financial ecosystem.

Primary Markets

Primary markets are where securities are initially issued by companies or governments. This is the first time these securities are offered to the public. Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), where a private company first sells its shares to the public, are a prime example of activity in the primary market. Similarly, governments issue bonds in the primary market to raise funds for public projects. The process typically involves an investment bank underwriting the offering, guaranteeing the sale of the securities to investors at a predetermined price. The proceeds from these sales directly benefit the issuer, providing them with the capital they need.

Secondary Markets

Secondary markets provide a platform for the trading of existing securities between investors. This means securities already issued in the primary market are bought and sold amongst investors. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the Nasdaq are prominent examples of secondary markets. These markets offer liquidity, allowing investors to readily buy or sell securities without having to rely on the original issuer. The price discovery mechanism in secondary markets, determined by the forces of supply and demand, provides valuable information about the perceived value of the securities. This price is crucial for both investors making investment decisions and companies assessing their market capitalization.

Securities Trading and Pricing

The trading of securities in secondary markets is facilitated through various mechanisms, including exchanges (organized markets with centralized trading) and over-the-counter (OTC) markets (decentralized trading networks). The price of a security is primarily determined by the interaction of buyers and sellers. Various factors influence pricing, including the company’s financial performance, industry trends, economic conditions, and investor sentiment. Sophisticated algorithms and high-frequency trading further complicate the pricing dynamics. For example, news about a company’s earnings exceeding expectations can lead to a surge in demand, driving up the price of its stock. Conversely, negative news might cause a price drop.

Regulation of Securities Markets

Securities markets are subject to extensive regulation to protect investors and maintain market integrity. Regulatory bodies, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States, oversee market operations, enforce disclosure requirements, and prevent fraud and manipulation. These regulations aim to ensure transparency, fairness, and efficiency in the markets. Regulations dictate the information companies must disclose to investors, the rules governing trading practices, and the requirements for market participants like brokers and investment advisors. The goal is to foster investor confidence and prevent market instability. For example, regulations mandate that companies disclose financial statements regularly, ensuring investors have access to the information they need to make informed decisions.

Investing in Securities

Investing in securities offers the potential for significant financial growth, but it also involves inherent risks. Understanding different investment strategies, assessing risk tolerance, and developing a well-defined plan are crucial for successful participation in the securities market. This section explores practical strategies for navigating the complexities of securities investment.

Diversifying a Securities Portfolio

Diversification is a fundamental principle of successful investing. It involves spreading investments across various asset classes to reduce the impact of poor performance in any single investment. By diversifying, investors aim to mitigate risk and enhance the overall portfolio’s potential for returns. A well-diversified portfolio might include a mix of stocks, bonds, and other asset classes, each with varying levels of risk and potential return. For example, a portfolio might allocate 60% to stocks (split between large-cap, mid-cap, and small-cap companies across different sectors), 30% to bonds (with a mix of maturities and credit ratings), and 10% to alternative investments like real estate or commodities. The specific allocation will depend on individual risk tolerance and financial goals.

Risk Assessment and Management

Risk assessment is the process of identifying and evaluating potential losses associated with investments. This involves considering factors such as market volatility, interest rate changes, and the financial health of the issuing companies. Risk management involves developing strategies to mitigate these potential losses. These strategies can include diversification, hedging (using financial instruments to offset potential losses), and setting stop-loss orders (automatically selling an investment when it reaches a predetermined price). For instance, an investor concerned about market downturns might choose to invest a portion of their portfolio in low-risk government bonds, which typically offer lower returns but are less susceptible to significant price fluctuations.

A Beginner’s Guide to Investing in Securities

Investing in securities can seem daunting for beginners, but a systematic approach can make it more manageable. First, define your financial goals – are you saving for retirement, a down payment on a house, or something else? This helps determine your investment timeline and risk tolerance. Next, research different investment options and understand their associated risks and potential returns. Start with a small amount of money you’re comfortable losing to gain practical experience. Consider using a robo-advisor or working with a financial advisor, especially if you’re new to investing. Robo-advisors offer automated portfolio management based on your risk tolerance and goals, while financial advisors provide personalized guidance. Remember to monitor your portfolio regularly and adjust your investment strategy as needed based on market conditions and your evolving financial circumstances. Regularly reviewing financial news and market trends is also beneficial.

Securities Regulation

The global financial system relies heavily on trust. Securities regulation is crucial for maintaining this trust by establishing a framework to protect investors and ensure the integrity of the markets. Without robust regulatory oversight, investors would be vulnerable to fraud, manipulation, and unfair practices, ultimately undermining the efficiency and stability of the entire financial system.

Securities regulation aims to create a level playing field, promoting transparency and accountability within the securities industry. This is achieved through a complex interplay of laws, regulations, and enforcement mechanisms designed to safeguard investors’ interests and maintain market confidence. This involves a variety of measures, from mandatory disclosures to strict rules governing trading practices.

The Role of Regulatory Bodies in Protecting Investors

Regulatory bodies, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the United Kingdom, and similar organizations worldwide, play a vital role in protecting investors. These bodies are responsible for overseeing securities markets, enforcing securities laws, and investigating potential violations. Their powers typically include conducting audits, imposing sanctions (fines, suspensions, or even criminal charges), and issuing cease-and-desist orders to prevent fraudulent activities. They also work to educate investors about their rights and responsibilities, thereby empowering them to make informed investment decisions. For instance, the SEC’s investor education website provides resources on various investment topics, helping investors navigate the complexities of the securities market.

The Importance of Disclosure Requirements

Full and accurate disclosure of material information is a cornerstone of securities regulation. This means companies issuing securities (stocks, bonds, etc.) are legally obligated to provide investors with all relevant information that could reasonably influence their investment decisions. This includes financial statements, risk factors, and any significant corporate events that might impact the value of the securities. The requirement for disclosure promotes transparency, allowing investors to assess the risks and potential rewards associated with an investment before committing their capital. Failure to meet disclosure requirements can lead to severe penalties, including fines and legal action from regulatory bodies. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 in the US, for example, significantly strengthened corporate disclosure requirements in the wake of major accounting scandals.

Legal Frameworks Governing Securities Trading

Securities trading is governed by a comprehensive body of laws and regulations designed to ensure fair and orderly markets. These frameworks cover a wide range of activities, including the registration of securities, the licensing of brokers and dealers, and the regulation of trading practices. Many jurisdictions have laws prohibiting insider trading, market manipulation, and other forms of fraudulent activity. These regulations are often enforced through civil and criminal penalties, aiming to deter misconduct and protect investors from unfair practices. The specific regulations vary across jurisdictions, but the overarching goal is to maintain market integrity and investor confidence. For instance, regulations surrounding short selling are designed to prevent manipulative trading practices that could destabilize markets.

Securities and the Economy

Securities markets play a vital role in the overall health and growth of an economy. Their impact is multifaceted, influencing everything from capital investment to monetary policy effectiveness. A robust and efficient securities market is a cornerstone of a thriving economy.

The existence of well-functioning securities markets significantly impacts economic growth. These markets provide a platform for companies to raise capital, enabling them to invest in expansion, research and development, and job creation. This increased investment fuels economic activity and drives overall growth. Conversely, poorly functioning or underdeveloped securities markets can hinder economic progress by limiting access to capital for businesses.

Securities and Capital Formation

Securities markets are the primary mechanism for facilitating capital formation. Businesses needing funds for expansion or new ventures can issue securities—like stocks and bonds—to raise capital from a wide range of investors. This process transforms savings into investment, a critical component of economic growth. For instance, a technology startup might issue stock through an Initial Public Offering (IPO), attracting investment to fund its growth and potentially creating new jobs in the process. This flow of capital from savers to businesses, facilitated by the securities market, is essential for long-term economic prosperity. Without efficient securities markets, many promising ventures would struggle to secure the necessary funding.

Securities and Monetary Policy

Monetary policy, implemented by central banks, aims to influence economic activity through interest rates and money supply. Securities markets are crucial to the effectiveness of monetary policy. Central banks often buy or sell government securities (like Treasury bonds) to adjust the money supply. For example, buying government bonds injects money into the market, lowering interest rates and stimulating borrowing and investment. Conversely, selling bonds removes money from circulation, increasing interest rates and potentially slowing down economic activity. The responsiveness of securities markets to these central bank actions is a key factor in the success of monetary policy. A liquid and efficient securities market ensures that monetary policy changes are transmitted quickly and effectively throughout the economy.

Securities Fraud: What Are Securities In Finance

Securities fraud encompasses a range of illegal activities designed to manipulate the financial markets for personal gain, often at the expense of unsuspecting investors. These actions undermine the integrity of the market and erode public trust in financial institutions. Understanding the various forms of securities fraud, their consequences, and preventative measures is crucial for maintaining a fair and efficient securities market.

Common Types of Securities Fraud, What are securities in finance

Several deceptive practices constitute securities fraud. These schemes exploit vulnerabilities in the regulatory system and investor psychology to achieve illicit profits. The consequences for perpetrators and victims alike can be severe.

- Insider Trading: This involves using confidential, non-public information to trade securities for profit. For example, a company executive buying shares before a positive earnings announcement, or selling shares before a negative announcement. This gives the insider an unfair advantage over other investors.

- Market Manipulation: This includes activities like spreading false or misleading information (pump and dump schemes) to artificially inflate or deflate a security’s price. A classic example is a coordinated effort to buy a large quantity of a stock, driving up the price, before selling at the inflated price, leaving other investors with losses.

- Fraudulent Offerings: This involves misrepresenting the value or prospects of a security in order to induce investors to buy. This could include exaggerating a company’s earnings, hiding significant liabilities, or making false promises about future performance.

- Churning: This is the excessive trading of a client’s account by a broker solely to generate commissions, regardless of the client’s investment objectives or the potential for losses. A broker might make numerous trades in a short period, resulting in high commissions but minimal, or even negative, returns for the investor.

Consequences of Securities Fraud

The repercussions of securities fraud are far-reaching and impact individuals, companies, and the broader economy. These consequences often involve significant financial penalties and legal ramifications.

- Financial Losses for Investors: Victims of securities fraud can suffer substantial financial losses, potentially leading to bankruptcy or significant hardship.

- Criminal Penalties: Perpetrators face imprisonment, hefty fines, and a criminal record, severely impacting their future prospects.

- Civil Penalties: Victims can sue perpetrators for damages, potentially recovering their losses plus additional penalties.

- Reputational Damage: Companies involved in securities fraud suffer reputational damage, leading to decreased investor confidence and potential business failure.

- Erosion of Market Confidence: Widespread securities fraud undermines trust in the financial markets, potentially leading to decreased investment and economic instability.

Measures to Prevent and Detect Securities Fraud

Preventing and detecting securities fraud requires a multi-faceted approach involving regulatory oversight, corporate governance, and investor awareness.

- Strong Regulatory Framework: Robust laws and regulations, enforced by competent authorities, are essential to deter fraudulent activities. This includes rigorous auditing procedures and prompt investigation of suspected fraud.

- Effective Corporate Governance: Companies should implement strong internal controls, independent audits, and ethical codes of conduct to prevent fraud within their organizations. A strong and independent board of directors plays a vital role in oversight.

- Investor Due Diligence: Investors should conduct thorough research before investing in any security, carefully reviewing financial statements and company disclosures. Seeking advice from a qualified financial advisor is also recommended.

- Whistleblower Protection: Protecting whistleblowers who report suspected fraud is critical to encouraging the reporting of illegal activities. Strong legal protections are necessary to ensure that whistleblowers are not retaliated against.

- Advanced Technologies: Utilizing advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, can help detect suspicious trading patterns and other indicators of fraud.

Outcome Summary

In conclusion, understanding what are securities in finance is fundamental to navigating the world of investing and comprehending the broader financial ecosystem. While the inherent risks associated with different securities vary significantly, careful consideration, diversification, and a solid grasp of the underlying principles can pave the way for informed decision-making. The dynamic nature of securities markets necessitates continuous learning and adaptation, emphasizing the importance of staying informed about market trends and regulatory changes.